London is without doubt one of the more unplanned big cities in the world. Not for us the sweeping boulevards and grand avenues of Paris or the Romanesque order of the grid systems of Manhattan, but instead a complex maze of streets, many dating from the medieval period.

But, whilst it may be true so say there was little in the way of “grand design” in the growth of London, by the same token little also happened completely by accident.

The gentlemen’s clubs of St James’s are a classic case in point. It is inconceivable that their explosive growth in the latter half of the 19th Century (there were maybe as many as 250 at their peak), their subsequent decline in the 20th century (currently around 50 remain) and their intense concentration in such a specific area could have been either a historical or geographical accident.

The gentlemen’s clubs of St James’s are a classic case in point. It is inconceivable that their explosive growth in the latter half of the 19th Century (there were maybe as many as 250 at their peak), their subsequent decline in the 20th century (currently around 50 remain) and their intense concentration in such a specific area could have been either a historical or geographical accident.

But why did they see such rapid growth when they did, and why did they “settle” where they did?

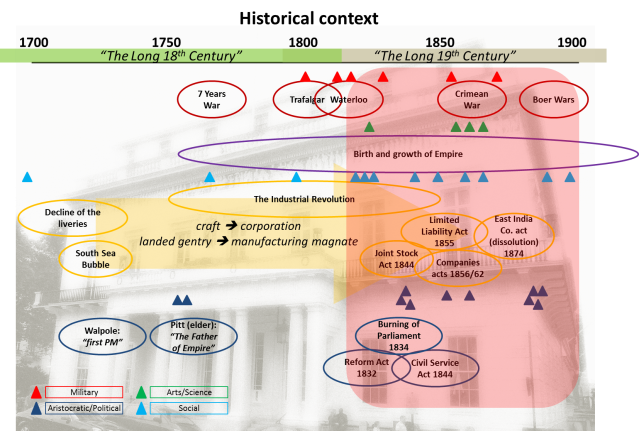

A consideration of the historical backdrop against which they appeared helps to answer the first of those questions:

These periods are characterised by British historians as “the long 18th century” and “the long 19th century”, as many of the larger British historical movements tended to straddle the standard calendar definitions.

It was a particularly belligerent period, there being no fewer than 5 major wars between the late 18th and the turn of the 19th century, but they did clear the way – quite literally as Britannia really did rule the waves and our merchant fleet could ply their trade relatively unencumbered – for the birth and growth of the British Empire.

On the industrial front, the former iron grip of the City livery companies over craft and trade in London had disappeared and the industrial revolution was born, grown and exported. Investors had been previously been burned by the South Sea bubble, but a raft of 19th century legislation formalised company formation and allowed entrepreneurs’ private wealth to be “distanced” from their investments in business. The East India Company, the quasi-military company that had dominated business and trade with the Empire was dissolved so everyone could get in on the action.

The net effects? The shape of industry changed fundamentally from being craft and trading based and saw the birth of industrialisation, mechanisation and “the corporation”. Had you met a man of real wealth at that start of the 19th century it was most likely to have been derived from land. By the end of the century, it was more likely to have come from industry.

The triangles on the above chart represent a sample of gentlemen’s clubs categorised into four broad types and plotted by foundation date. This clearly demonstrates quite how much they were “of” the (largely) Victorian period (as highlighted by the red box) with around 75% of the sample being founded in that era.

But why might that be?

Leonore Davidoff in her book The Best Circles described what she called “the Victorian Social Dance”, a complex and constraining code of social etiquette that the aristocratic and middle classes had to endure in building a set of acquaintances:

“The first step was to be introduced; preferably the person with the higher status would have first been asked if he or she wished to be introduced. The next step was generally calling and leaving one’s cards to which visit the hostess would answer whether or not she was ‘At Home’. These calls between acquaintances took place in the middle of the afternoon with the time depending whether it was a ceremonial, semi-ceremonial or intimate call. Etiquette prescribed that calls should be short, about fifteen minutes, during which time the callers kept on their outdoor clothing. The calls might then be followed by an invitation to dinner. Frequently absences could be used to change an individual’s or family’s social milieu, sometimes radically, for instance by going abroad. On returning from such an absence, the choice of whom to call on could be used to form a new social set.”

Now if you were a young buck with ideas and ambitions to make your way, you needed to meet the “right” people, but you didn’t have the time for such social niceties whilst everyone else was making the money. However, Victorian social convention dictated that certain rules still had to be followed, and marrying these two seemingly disparate forces is where the St James’s gentlemen’s clubs really came into their own.

The clubs offered the chance to by-pass this “social dance” and gave easier opportunities to network, but still in a suitably controlled environment that helped satisfy the strict social codes of Victorian society (the club membership selection processes acting as a guarantee of the “soundness” of the people you met).

At the same time, they offered: privacy – both from the outside world and an assurance of the discretion of fellow members; communication – both in terms of networking, news and gossip and the fact that they were early adopters of new communications technology such as the telegraph and telephone; and status – membership was a form of qualification as a “gentleman” (and offered a grand townhouse for those that couldn’t afford their own).

The other driver of their growth was the politics of the age. Whilst the early clubs such as the Travellers, the Union and the Portland explicitly disavowed any political allegiance two major events were to prompt an explosion in the formation of political clubs.

The first was the Reform Act of 1832. The Conservative party took such a beating at the  first election after the widening of the voting franchise that they identified an urgent need to re-organise. James Cornford in his book The Transformation of Conservatism in the Late 19th Century described the Carlton Club as being created with the aim of providing “a meeting place, a convenient social setting for the very personal business of party management”, which became true of all the many political clubs formed at the time.

first election after the widening of the voting franchise that they identified an urgent need to re-organise. James Cornford in his book The Transformation of Conservatism in the Late 19th Century described the Carlton Club as being created with the aim of providing “a meeting place, a convenient social setting for the very personal business of party management”, which became true of all the many political clubs formed at the time.

The second was the burning down of Parliament in 1834, which left MP’s without a home and nowhere for the whips to gather them, so many of the clubs became de facto party offices.

Once the principle of “club as party office” had been established, a rash of clubs with explicit political allegiances sprang up to the point where by 1890 50% of total club membership was of political clubs and at least 90% of sitting MP’s were members of at least one club (being elected to parliament was, in fact, the most effective way to jump the long waiting lists of the most exclusive clubs as MPs were considered “supernumerary” to otherwise strict membership caps).

The character of political groupings also changed fundamentally between the 18th and 19th centuries, from small “acquainted” (related, even) groups of 25-30 people to wider circles of hundreds which inevitably would include strangers.

This naturally required larger premises in which to meet and led to the grand halls, atria (something which all subsequent clubs copied from the Athenaeum, the first to have a grand atrium) and meeting rooms which are so characteristic of the clubs’ internal architecture.

This naturally required larger premises in which to meet and led to the grand halls, atria (something which all subsequent clubs copied from the Athenaeum, the first to have a grand atrium) and meeting rooms which are so characteristic of the clubs’ internal architecture.

So why St James’s?

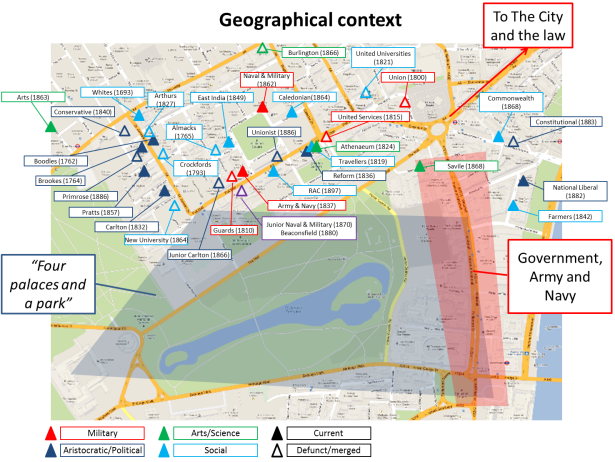

The illustration below reveals quite how concentrated they were in this area (the clubs sampled are the same ones as represented on the “historical context” illustration):

The simple answer is, given their purpose, why really would they go anywhere else?

Living In an age of instant mass communication and rapid transport as we do today, it is easy to forget the value of proximity. What you see above was the LinkedIn of its day, but it all needed to be within ideally walking, but at worst a short horse and carriage ride distance.

They needed to be close to the seats of royal, governmental and military power in the “four palaces and a park” heart of Westminster. Settling just to the north of those also made practical sense for ease of access to the legal “village” at the Inns of Court off the Strand and Fleet Street, the financiers of the City and the prime residential districts of Mayfair and Belgravia to the north and west respectively.

Given that so many of the clubs were effectively used as political party offices, the location was also handy for MP’s needing a “respectable” London address and even handier for the whips as they knew where their members were when needed for a vote without having to search dozens of West End haunts.

There were also practical reasons. When Carlton House (which occupied a great part of the northern flank of St James’s Park) was demolished in 1825, it was decided to sell some of the the land it occupied as small parcels, so there were affordable plots to be had.

At the turn of the 20th century the clubs fell into fairly rapid decline.

One of the reasons was that they became victims of their own popularity. Waiting lists were so long at some of the more exclusive clubs that parents eager to get their sons in would put them on the list the day they were born, but many not willing to wait simply set up their own. This eroded their key selling point – the cachet of exclusivity – and ultimately led to their decline.

At the same time the rapid expansion of rail-based public transport (trains, underground and electric trams) and the installation of telephone exchanges in every major city between them reduced the necessity for proximity and the political parties were establishing dedicated management structures and party HQ’s. As such. their raison d’etre as the hub of social, business and political networks diminished rapidly.

They have experienced something of a resurgance since the 1980’s (based largely on City money), but they were so much “of their time” that they will never again reach their Victorian heyday.

But they have left behind some of the most stunning Georgian and Victorian neo-classical architecture in London and many a tale to be told.

(Reference note: I am indebted to a lecture I attended by Seth Thévoz at the Royal Overseas League in November 2012 for many of the facts and figures on the political role of the St James’s clubs. You can discover more about Seth’s extensive research in this field and elsewhere at his website here).

Great article! On several walking tours, the guide has pointed out some of the Gentlemen’s Clubs but never explained their history. Now I know…

Thank you so much for your kind comment, much appreciated. The piece grew out of an assessed walk design exercise for the Westminster guiding course I’m currently on. I set out to look for evidence of specific Victorian business networks that might have been based around the clubs, but when I discovered quite how historically and geographically “clustered” they were, the urban geographer in me just had to find out why that might be! I’m planning on promoting a walk on the subject myself as soon as I gain my Westminster badge (this May/June, all being well).

Thank you, much appreciated. Love your blog and am now following.